Good morning Blue Roomies, and welcome to lots of new folks this week!

It’s summertime here in the Blue Room, which means on Fridays I’ll be alternating my own work with “lite” posts such as photos, quotes, etc.

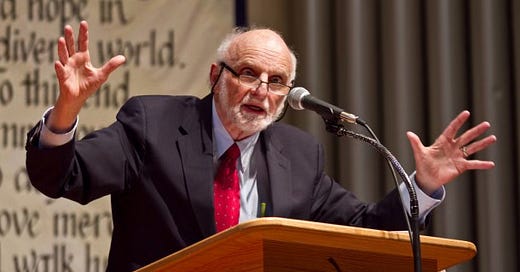

This one is anything but lite, however, as it’s a piece by Walter Brueggemann, a true giant of Old Testament scholarship, who died yesterday morning at age 92.

Every single interaction I had yesterday with a clergy person, and there were several, referenced his death and what his writing meant to us.

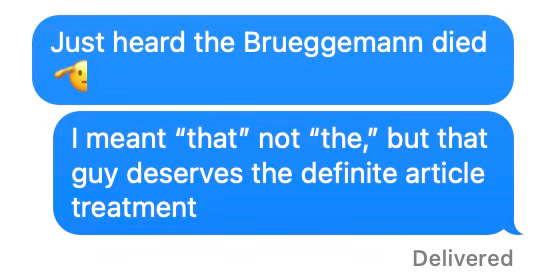

I texted this to a friend when I heard:

Yep. The Brueggemann for sure. Though my clergy group cites him so much in our papers we’ve taken to calling him “Uncle Walt.” Several of us had him while we were at Columbia Seminary; I took his Psalms class and found him brilliant and thoroughly intimidating. Still do… never has my imposter syndrome flared up so badly as when I was asked to blurb his book on hope two years ago. (By the way, the man was wildly prolific. In his prime, it felt like he put out a book a week. I was always reminded of this silly SNL bit where Jon Lovitz plays Stephen King, furiously tapping on his typewriter while simultaneously answering questions by Weekend Update’s Dennis Miller.)

I went into my files to see what I had of Brueggemann that might be appropriate to share with you today. I’m not sure where this piece came from; it appears to have been written in 1999, but it might as well have been written last week. Greed, exploitation of the vulnerable by the wealthy, the co-opting of religion by the powers and principalities—it’s all here. I’ve edited this down from its original length. I urge you to read it at a reflective pace, which is what his work deserves.

The majority of the world’s resources pour into the United States. And as we Americans grow more and more wealthy, money is becoming a kind of narcotic for us. We hardly notice our own prosperity or the poverty of so many others. The great contradiction is that we have more and more money and less and less generosity—less and less public money for the needy, less charity for the neighbor.

MAMD interjection: Perhaps you’ve seen this video of Scott Galloway and his quiet yet forceful takedown of the world’s richest man. If not, I’ve clipped the pertinent bit here. (Note, the first few seconds have no sound, but once Scott starts talking it appears to be fine.)

Back to The Brueggemann:

Though many of us are well intentioned, we have invested our lives in consumerism. We have a love affair with “more”—and we will never have enough. Consumerism is not simply a marketing strategy. It has become a demonic spiritual force among us, and the theological question facing us is whether the gospel has the power to help us withstand it.

The Bible starts out with a liturgy of abundance. Genesis 1 is a song of praise for God’s generosity. It tells how well the world is ordered. It keeps saying, “It is good, it is good, it is good, it is very good.” It declares that God blesses—that is, endows with vitality—the plants and the animals and the fish and the birds and humankind. And it pictures the creator as saying, “Be fruitful and multiply.” In an orgy of fruitfulness, everything in its kind is to multiply the overflowing goodness that pours from God’s creator spirit. And as you know, the creation ends in Sabbath. God is so overrun with fruitfulness that God says, “I’ve got to take a break from all this. I’ve got to get out of the office.”

Later in Genesis God blesses Abraham, Sarah and their family. God tells them to be a blessing, to bless the people of all nations. Blessing is the force of well-being active in the world, and faith is the awareness that creation is the gift that keeps on giving. That awareness dominates Genesis until its 47th chapter. In that chapter Pharaoh dreams that there will be a famine in the land. So Pharaoh gets organized to administer, control and monopolize the food supply. Pharaoh introduces the principle of scarcity into the world economy. For the first time in the Bible, someone says, “There’s not enough. Let’s get everything.”

Martin Niemöller, the German pastor who heroically opposed Adolf Hitler, was a young man when, as part of a delegation of leaders of the Evangelical Lutheran Church, he met with Hitler in 1933. Niemöller stood at the back of the room and looked and listened. He didn’t say anything. When he went home, his wife asked him what he had learned that day. Niemöller replied, “I discovered that Herr Hitler is a terribly frightened man.”

Because Pharaoh, like Hitler after him, is afraid that there aren’t enough good things to go around, he must try to have them all. Because he is fearful, he is ruthless. Pharaoh hires Joseph to manage the monopoly. When the crops fail and the peasants run out of food, they come to Joseph. And on behalf of Pharaoh, Joseph says, “What’s your collateral?” They give up their land for food, and then, the next year, they give up their cattle. By the third year of the famine they have no collateral but themselves. And that’s how the children of Israel become slaves—through an economic transaction. (MAMD adds: an economic transaction, and an anxious desire for security no matter what the cost.)

By the end of Genesis 47 Pharaoh has all the land except that belonging to the priests, which he never touches because he needs somebody to bless him. The notion of scarcity has been introduced into biblical faith. The Book of Exodus records the contest between the liturgy of generosity and the myth of scarcity—a contest that still tears us apart today.

The promises of the creation story continue to operate in the lives of the children of Israel. Even in captivity, the people multiply. By the end of Exodus 1 Pharaoh decides that they have become so numerous that he doesn’t want any more Hebrew babies to be born. He tells the two midwives, Shiphrah and Puah (though we don’t know Pharaoh’s name, we know theirs), to kill all the newborn boys. But they don’t, and the Hebrew babies just keep popping out.

By the end of Exodus, Pharaoh has been as mean, brutal and ugly as he knows how to be—and as the myth of scarcity tends to be. Finally he becomes so exasperated by his inability to control the people of Israel that he calls Moses and Aaron to come to him. Pharaoh tells them, “Take your people and leave. Take your flocks and herds and just get out of here!” And then the great king of Egypt, who presides over a monopoly of the region’s resources, asks Moses and Aaron to bless him. The powers of scarcity admit to this little community of abundance, “It is clear that you are the wave of the future. So before you leave, lay your powerful hands upon us and give us energy.” The text shows that the power of the future is not in the hands of those who believe in scarcity and monopolize the world’s resources; it is in the hands of those who trust God’s abundance.

When the children of Israel are in the wilderness, beyond the reach of Egypt, they still look back and think, “Should we really go? All the world’s glory is in Egypt and with Pharaoh.” But when they finally turn around and look into the wilderness, where there are no monopolies, they see the glory of Yahweh.

In answer to the people’s fears and complaints, something extraordinary happens. God’s love comes trickling down in the form of bread. They say, “Manhue?”—Hebrew for “What is it?”—and the word “manna” is born. They had never before received bread as a free gift that they couldn’t control, predict, plan for or own. The meaning of this strange narrative is that the gifts of life are indeed given by a generous God. It’s a wonder, it’s a miracle, it’s an embarrassment, it’s irrational, but God’s abundance transcends the market economy.

Three things happened to this bread in Exodus 16. First, everybody had enough. But because Israel had learned to believe in scarcity in Egypt, people started to hoard the bread. When they tried to bank it, to invest it, it turned sour and rotted, because you cannot store up God’s generosity. Finally, Moses said, “You know what we ought to do? We ought to do what God did in Genesis I. We ought to have a Sabbath.” Sabbath means that there’s enough bread, that we don’t have to hustle every day of our lives. There’s no record that Pharaoh ever took a day off. People who think their lives consist of struggling to get more and more can never slow down because they won’t ever have enough.

When the people of Israel cross the Jordan River into the promised land the manna stops coming. Now they can and will have to grow their food. Very soon Israel suffers a terrible defeat in battle and Joshua conducts an investigation to find out who or what undermined the war effort. He finally traces their defeat to a man called A’chan, who stole some of the spoils of battle and withheld them from the community. Possessing land, property and wealth makes people covetous, the Bible warns.

We who are now the richest nation are today’s main coveters. We never feel that we have enough; we have to have more and more, and this insatiable desire destroys us. Whether we are liberal or conservative Christians, we must confess that the central problem of our lives is that we are torn apart by the conflict between our attraction to the good news of God’s abundance and the power of our belief in scarcity—a belief that makes us greedy, mean and unneighborly. We spend our lives trying to sort out that ambiguity.

Jesus said it succinctly. You cannot serve God and mammon. You cannot serve God and do what you please with your money or your sex or your land. And then he says, “Don’t be anxious, because everything you need will be given to you.” But you must decide. Christians have a long history of trying to squeeze Jesus out of public life and reduce him to a private little Savior. But to do this is to ignore what the Bible really says. Jesus talks a great deal about the kingdom of God—and what he means by that is a public life reorganized toward neighborliness.

As a little child Jesus must often have heard his mother, Mary, singing. And as we know, she sang a revolutionary song, the Magnificat—the anthem of Luke’s Gospel. She sang about neighborliness: about how God brings down the mighty from their thrones and lifts up the lowly; about how God fills the hungry with good things and sends the rich away empty. Mary did not make up this dangerous song. She took it from another mother, Hannah, who sang it much earlier to little Samuel, who became one of ancient Israel’s greatest revolutionaries. Hannah, Mary, and their little boys imagined a great social transformation. Jesus enacted his mother’s song well. Everywhere he went he broke the vicious cycles of poverty, bondage, fear and death; he healed, transformed, empowered and brought new life. Jesus’ example gives us the mandate to transform our public life.

Everywhere Jesus goes the world is rearranged: the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor are freed from debt. The forgiveness of debts is the hardest thing to do—harder even than raising the dead to life. Jesus left ordinary people dazzled, amazed, and grateful; he left powerful people angry and upset, because very time he performed a wonder, they lost a little of their clout. The wonders of the new age of the coming of God’s kingdom may scandalize and upset us. They dazzle us, but they also make us nervous. The people of God need pastoral help in processing this ambivalent sense of both deeply yearning for God’s new creation and deeply fearing it.

The profane is the opposite of the sacramental. “Profane” means flat, empty, one-dimensional, exhausted. The market ideology wants us to believe that the world is profane—life consists of buying and selling, weighing, measuring and trading, and then finally sinking down into death and nothingness. But Jesus presents an entirely different kind of economy, one infused with the mystery of abundance and a cruciform kind of generosity.

It is, of course, easier to talk about these things than to live them. Many people both inside and outside of the church haven’t a clue that Jesus is talking about the economy. We haven’t taught them that he is. But we must begin to do so now, no matter how economically compromised we may feel. Our world absolutely requires this news. It has nothing to do with being Republicans or Democrats, liberals or conservatives, socialists or capitalists. It is much more elemental: the creation is infused with the Creator’s generosity, and we can find practices, procedures and institutions that allow that generosity to work.

What I’m Up To

Here’s last Sunday’s sermon—manuscript and audio. Earthquakes and empires.

Steady on.

I am a day late reading about The Breuggemann's death. I guess I thought he might live forever. I was a senior at Columbia when he arrived, but was able to take a class on the Pentatuch when I was doing further study for pastoral counseling, and heard him speak at many conferences. Thank you for your tribute and sermon. I shall grieve knowing he is no longer challenging us. Pity we Presbyterians can't name saints. Thank you for sharing.

I had never really thought about Mary singing that song to Jesus. What a beautiful idea.

The Brueggemann will be missed but what a powerful, prophetic, and beautiful legacy he has left.