Hello Blue Roomies,

This week I moved into the next phase of book writing, a bit more intense than before. I’ll be in this phase for the rest of the summer. Good thoughts appreciated!

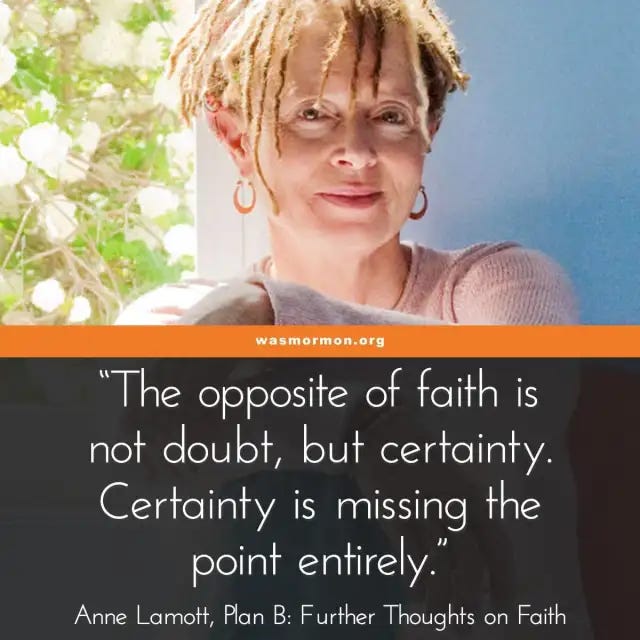

As a reminder, the new book consists of a series of paired chapters: the first chapter in each pair describes a value we see in the world as it is, a value that upholds unhelpful and oppressive ideas of what “normal” is. The second chapter in each pair explores a transformational value that provides an antidote to the first. This week, as I’ve been writing about certainty, I found this piece in some old writing. It’s still in draft form, and as you will see, it references events from the late 2000s. As far as I know, I’ve never shared it, but am offering it now to supporting subscribers. Obviously the themes I’m currently writing about are things I’ve struggled with for a long time!

Also, a reminder that we’ll have our next book talk for supporting subscribers on Monday, June 24 at noon EDT. Zoom link is at the bottom of this post. Join us for 30-40 minutes of freestyle conversation about one or more themes from the book—warm and thought-provoking for all, and very helpful for me as I write. (And hey, everyone who participates in one or more book talks will get a shoutout in the book’s acknowledgements!)

And now, a piece from the archives:

~

Jesus’ death on the cross is not some isolated anomaly, the arrow that found God’s one unprotected human place amid all that divine armor. The cross is fundamental to who God is—a self-limiting God, a God who is willing to be acted upon, and even to suffer and yes, to change.

Several years ago, the interstate 35 bridge in Minneapolis collapsed, killing 13 people. Later that week, a friend sent me a blog post about the incident. She was not a Christian and asked me, “What do you think about this? Is this the God of your religion?” The post was by John Piper, a writer/theologian, who was describing a conversation with his 9 year old daughter about the bridge collapse:

“But you and I know that God did not do anything wrong,” he said to his daughter. “God always does what is wise. And you and I know that God could have held up that bridge with one hand.”

Talitha said, “With his pinky.” “Yes,” I said, “with his pinky. Which means that God had a purpose for not holding up that bridge.”

What can I say? That view of God is not the one I believe in, and this is not the kind of bedtime conversation I would ever have with my kids. But I do recognize this God. It’s the one I grew up with, and is the God who shows up in the form of easy (but horrific) answers to terrible tragedies.

I grew up in a conservative Christian denomination in a congregation whose motto was “a fellowship of love.” The people there were nice enough, as I recall, but underneath it all was a theology of eternal damnation that came through in lots of different ways. It was made clear to me that my eternal salvation was dependent on my praying the so-called sinners’ prayer. There was a specific formula to it: I was a sinful person, I acknowledged that only Jesus could save me from an eternity of hell, and by accepting Jesus as my Lord, I would be spared that fate and go to heaven. Thanks be to God, Amen.

Once I prayed the sinners’ prayer, I got what a friend of mine who grew up in the same tradition now calls the Golden Ticket. But the risk of endless punishment from a vengeful God made me anxious. How could the all-powerful God of the universe be swayed by my one little prayer? I was taught that you only needed to be saved once, but what if all these well-intentioned people were wrong, and the single prayer wasn’t enough? And what if I got the prayer slightly wrong, or wasn’t sufficiently repentant the first time, or did something that was so bad it nullified the prayer? I got worried enough that I took to accepting Christ as my Lord and Savior every week, just to be sure. Heaven insurance.

Only as I got older did I start to question why God would set things up this way. I began to learn the big words to describe the God of my childhood—immutable, eternal, unchanging, omniscient (all-knowing). This God was large and in charge. Why would God be bound by my little action or inaction? Was God not free to do as God wanted? Did I possess some meagre handcuffs that somehow constrained God based on my prayer as an eleven year old? Not to mention the billions of people who not only weren’t Christian, but who may not have even heard the message of Jesus to have the option of praying the prayer. Was God really not free to save them? Wasn’t God supposed to be sovereign?

The older I got, the more I realized how two-dimensional this God of my childhood was. I heard people share well-intentioned platitudes about God’s plan, but those bromides did nothing for me. In fact, I grew increasingly hostile to them. I believe that good can come in the wake of suffering—I’ve seen it again and again, and in the pages of scripture, no less. But I don’t see much that’s righteous about a God who would arrange for terrible things to happen in order to bring about other, hopefully less terrible things.

In an article in the New York Times, Kate Bowler reflects about the experience of having terminal cancer at a young age, with a young child at home. [Editor’s note: she’s written so many books since then, but it all started with this NYT piece!] Bowler is a professor and historian who for many years studied the prosperity gospel, the idea that God blesses those whom God favors. The prosperity gospel isn’t exactly the theology I grew up with, but the two are kindred cousins. Bowler writes:

A neighbor knocked on our door to tell my husband that everything happens for a reason.

“I’d love to hear it,” my husband said.

“Pardon?” she said, startled.

“I’d love to hear the reason my wife is dying,” he said, in that sweet and sour way he has.

And that’s the rub. “Everything happens for a reason” sounds reasonable until you’re on the hook to supply that reason.

“The prosperity gospel has taken a religion based on the contemplation of a dying man and stripped it of its call to surrender all. Perhaps worse, it has replaced Christian faith with the most painful forms of certainty.”

After a childhood faith that promised me certainty, yet simultaneously failed to deliver—I don’t want certainty anymore.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Blue Room with MaryAnn McKibben Dana to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.